A creative way to develop students’ confidence in writing is to provide collaborative opportunities to jointly construct texts with their peers (HITS Strategy 5) and with the teachers (VCELT420).

This is described as Collaborative Learning. This strategy supports students to discuss their language choices, to consider the structure, purpose and genre of the texts before they create their own texts individually.

There are a range of ways in which teacher might approach the co-construction of texts, two of these are outlined below:

Co-constructing a text response paragraph

- After planning an essay on the board with the class, and providing a sample introduction, the teacher breaks student up into groups of four.

- Each group is allocated one of the body paragraphs of the essay to write (some groups may write the same paragraph).

- Each person in the group has responsibility for a sentence or sentences relating to the parts of the paragraph:

-

Topic sentence

-

Evidence

-

Explanation

-

Link.

The group plans the paragraph before each student writes their sentence/s into a shared digital space.

See below a sample of a co-constructed paragraph on Robert Newton’s novel Runner. The topic is ‘After losing his own father, other characters come to represent a father figure for Charlie. Discuss’.

Paragraph 1

Mr Peacock was supposed to act like a father to Charlie when his own father died.

Early in the novel, we see Mr Peacock honouring the promise by allowing Charlie to take home splinters and bark from the timber yard in return for raking it on Saturday morning. However, it soon becomes clear that Mr Peacock is interested in Ma, and when she doesn’t return is interest, he refuses Charlie the wood saying: “There’s no wood fer ya today. Go home and tell yer ma. And tell ‘er I’ll be calling tomorra’”.

Rather than being a kind father figure Mr Peacock becomes an abusive man in their house, forcing himself on Ma. Charlie saves Ma from him by knocking him out with a cricket bat.

Although he sits in his father’s chair, Mr Peacock is not a suitable father figure for Charlie.

The paragraph is edited by the group before it is sent to the teacher, who assembles the whole essay. Students then edit the text as a whole in their groups (complete with teacher’s introduction) and write a conclusion together.

Co-constructing a free-form poem

This activity uses a range of structured activities to encourage students to engage with poetry and consider word choice. The purpose of these activities is to provide a constraint that can serve to enable students by directing their creativity toward a very specific task. Where permitted, students will need a device that takes photographs to complete this activity.

Step by step guide:

- The teacher takes students to a chosen location in the school (locker bays, canteen, sports oval, gymnasium)

- Students take two photographs on their walk.

- Students return to the classroom where they record one word that describes each of their photographs. This word might be literal or figurative (There is scope here to be specific, for example, an adjective).

- In groups of 4, each student writes one word for the two photos of three other students. So, each student should have 8 words in total. If it is not possible to take photographs, the teacher can show the class a selection of images, and students can write four words in response to some of the images to get to this stage.

- The group of 4 jointly construct a poem using the 32 words of the group members. They are also able to use four verbs in any form (for example, run, running, ran); two articles (for example, a, an, the); and two conjunctions (for, because, etc.). The students select these eight additional words.

- Students develop a shared reading (interpretation) of the poem

- They record the poem in print or digital form

- Share the poem with the whole group through an oral presentation of the poem

- Walk around the room and read the poems of others at their own pace

- Return to their tables and use a software program to create a multimodal version of the group poem that includes the photos taken.

Deconstructing argument (reading and viewing, speaking and listening)

Helping students to identify and deconstruct arguments within persuasive texts is a pivotal skill in English. Any text that argues a position will contain a main argument as well as supporting arguments, and one way to help unpack the meaning within persuasive, argumentative and opinion writing is through deconstruction.

Deconstruction, also known as modelling, is a form of explicit teaching (HITS Strategy 3). Teachers can jointly deconstruct an argument or image with students to model how an argument is constructed and used to impact readers.

The first step is to help students to identify the argument within the text. One way to approach the teaching of argument is to pose this question of the text:

- What is the author trying to convince me of?

Jointly deconstructing an argument

To jointly deconstruct an argument:

- The teacher presents a paragraph from a persuasive text to the class. Before zooming in to the paragraph level, the teacher can briefly discuss and annotate the whole text, looking at the different paragraphs in the argument and the purposes achieved by each. This contextualises the paragraph into the larger picture of the argument as a whole.

- The teacher introduces the paragraph that will be focused on, and that the focus of the lesson is on looking at the specific word choices and how they work in the paragraph.

The example here is taken from ‘This is D-Day for the nation’s recycling crisis’.

In the past 18 months other states have progressively deteriorated as the weaknesses in their programs have been revealed. Victoria only recycles 37 per cent of municipal waste, according to a recent report by Infrastructure Victoria – a far cry from the bloated claims of previous years.

- The teacher reads the paragraph aloud to the class.

- The teacher asks students to offer a summary and interpretation of the paragraph through prompting questions (e.g. “What is the main idea in the paragraph?”, “What is the main point or argument being put forward?”).

- Select language choices from the extract to highlight and discuss their impact.

- The teacher annotates the paragraph according to the students’ responses, adds to or corrects the students’ interpretations, modelling how to identify the argument and to make meaning to interpret and read the text. At this stage, the teacher talks through her/his thinking.

- The teacher checks for student understanding during the joint deconstruction and at the end of the session.

Students may also be encouraged to annotate their own paragraph, as they read, speak and think through it.

A similar process can be applied to deconstructing images. For example, teachers may select an image that accompanies a passage of written text and jointly deconstruct it with a class or in small groups. This activity is also known as close reading.

This approach aligns with several curriculum links focused on comprehending arguments, including

VCELT425,

VCELY449,

VCELT436.

Literacy in Practice Video: English - Image Analysis

In this video, the teacher uses a visual image to jointly interpret and analyse the text with the support of the LIE strategy to make literal, inferential and evaluative interpretations and analysis of image texts.

Read the in-depth notes for this video

Reading journal and independent reading (reading and viewing, writing)

While independent reading allows students the time to engage in sustained and uninterrupted reading, it is helpful for students to note down their ideas, thoughts, responses and comments to a text as they read. While this can be done through annotation and close reading, reading journals provide students with opportunities to engage more deeply and reflectively with a text.

Student think-aloud processes can be used to scaffold journal writing. Students can be supported to pause their reading to:

- summarise what they have just read

- ask a question about the content

- identify new words and predict their meaning

- make a connection to an earlier part of the reading

- draw an image of what they have read

- write a poem or short story responding to the text

- extend the text by adding a prologue or conclusion.

Writing journals are often personal, so teachers may or may not choose to read or assess them formally. However, encouraging students to write them provides opportunities for students to develop both their reading comprehension of a text and their writing skills as they respond to what they have read.

Students can record their answers in a reading journal or as annotations on the text. Below is a student journal written by a Year 9 student after they have read Nyadol Nyuon’s ‘Her Mother’s Daughter’ from the anthology, Growing up African in Australia (Heiss, 2018).

The student’s writing links to the following Content Descriptions:

VCELA429,

VCELT439,

VCELY442,

VCELY443,

VCELY444.

Selecting and incorporating evidence and quotes (reading and viewing, writing)

Throughout the writing process, students will often be required to support their position or view with evidence. Teaching students about the different forms of evidence that can be used, and how to embed their evidence into their writing, is an important skill.

The way a student is able to summarise or paraphrase a specific moment in the text and/or embed a quotation into their writing has a significant impact on the overall fluency and cohesion of the final piece.

One way to approach how to use evidence is to employ explicit teaching strategies (HITS Strategy 3). Teachers can show students the clear distinctions between the different types of evidence that can be used, such as an example that is provided in the student’s own words, and the use of a key quote to support a point. This can be achieved through teacher modelling, the use of worked examples (HITS Strategy 4) and multiple exposures (HITS Strategy 6).

Ways to work with examples

A way that teachers can support students to comprehend and select examples from a text is to provide a short, worked example followed by an opportunity to apply new knowledge through the completion of a grid.

This strategy involves:

- the teacher providing the key quotation in the first instance

- students paraphrasing the event, that is, the context surrounding the quote in their own words

- the students finding the quote that matches the example.

Evidence Grid

|

Example |

Content |

|---|

| “There’s no wood fer ya today. Go home and tell yer ma. And tell ‘er I’ll be calling tomorra.” | Early in the novel, Mr Peacock honours his promise to Charlie’s late father, by allowing Charlie to take home splinters and bark from the timberyard in return for raking it on Saturday morning. However, it soon becomes clear that Mr Peacock is interested in Ma, and when she does not return his interest, he refuses to help Charlie anymore. |

Teacher comment:

This quote is clearly placed in the context of the moment in the novel when Charlie is let down by Mr Peacock, even though he had promised to look after the young boy and his mother. Although he had demonstrated acts of kindness towards Charlie, in the end, he is out for his own gain.

Evidence Grid

|

Example |

Content |

|---|

| “…as quick as flicking a switch, Squizzy turned nasty.” | |

| Charlie saves Ma from Mr Peacock by hitting him with a cricket bat. |

| “…in the seedy streets of Richmond, you would not find two finer neighbours than the Redmonds.” | Unlike the other men in his life such as Mr Peacock and Squizzy, Mr Redmond is a caring, paternal figure. He offers Charlie advice and boxing training. |

| “It ain’t just the runnin’, Mr Redmond, ya done so much fer us, I don’t know where we’d be without ya.” | |

Curriculum link for the example above:

VCELT409.

Ways to work with quotations

Long slabs of quoted material should to be avoided, so students need clear instructions about what to include when using quotes in their work.

Key terms

Quotation marks: a pair of punctuation marks “ ” or ‘ ’ indicate the beginning and end of a quotation where the exact words of another text are directly cited or referenced.

Ellipsis: … three dots or marks (such as…) are used to indicate an omission of words from a phrase without changing the meaning of the original text.

Tips for using quotations

- Enclose quotes in quotation marks.

- Modify quotes where necessary. When the exact quote does not fit a sentence , leave out parts of it in order to emphasise others, or to substitute other words (for instance, to change the tense or to identify a character) for greater clarity.

- Substitute words in quotes where required. For example, change ‘I’ to ‘he’ or ‘she’. Substituting words will not alter the meaning of a quote.

- Include quotes into the flow of your own discussion.

Provide students with a range of opportunities to practice applying the different conventions associated with the use of quotations in their own texts.

Example: The Sapphires directed by Wayne Blair.

Punctuation activity

Insert the correct punctuation into the following quotations:

- I would lay down my life before I let any harm befall those girls

- Youve let Julie run off to Melbourne havent ya

- Nothing but the best for our stars baby

- If you people worked as much as you fished youd be really rich you know

- Just so as ya know youre all standing on blackfella country.

Ellipsis, modification and substitution activity

Using the model below, insert ellipses and modify the following quotations:

Model

“You think you can walk away from your mob? Live in the city for 10 years, making out you’re a gubba and then get up on stage and say you’re a black fella and that’s alright? Nah, it’s not alright with me.” “You think you can walk away from your mob? Live in the city for 10 years… then get up on stage and say you’re a black fella and that’s alright?...

Task

- “Because I didn’t have a place, and then I met these crazy Aboriginal girls and one amazing woman and I had a place and I liked it. So, if I’ve ruined all of that, then I’m an idiot. But you knew that already.”

- “They’re having some problems over there at the minute, but I’d imagine that the girls would be miles away from any of the fighting. And there’d be armed guards, of course. Marines whose sole task is to watch over the girls.”

- “Take her from her family, put her in an institution, teach her white ways. Pretty soon there’ll be no black fellas left to worry about.”

Incorporating quotes activity

Using the models below, re-write the sentences as one sentence, incorporating the quote:

Models

- Dave teaches the girls to “loosen up” on stage by telling them to “Just feel the music!”

- Gail also encourages the group to continue and to keep believing in themselves when things become challenging, when she says, “We’ve got the voices, now let’s shine.”

Task

- Cynthia and Gail are trying to catch a ride into town, but the drivers ignore them and drive on. “Cause we are black and stupid.”

- Kay is taken from her home at a young age and wants to be black. “Going out with a black fella is not going to make you any blacker, Kay.”

- “Just so we are clear Robby, I’m black. I’m just… pale black.” Kay say to Robby she is going out with.

Curriculum links for the above example:

VCELA414,

VCELY450.

Structuring persuasive language analysis (writing)

As well as being able to identify and deconstruct arguments within persuasive writing, students are required to analyse the language techniques used by the writer. One approach used to get students thinking about persuasive language techniques is to pose this question of the text:

-

How is the author trying to convince the reader?

Students learn about the use of persuasive language by receiving a clear set of definitions and examples of persuasive techniques.

This allows students to become familiar with such strategies in a range of contexts. These persuasive techniques will need to be encountered and revisited on multiple occasions. This teaching strategy is called Multiple Exposures (HITS Strategy 6).

Persuasive technique grid

Example: Persuasive technique grid

|

Technique |

Definition |

Example |

|---|

| Attack | An attack is used to denigrate an opponent. it is used to undermine, insult or embarrass opposition. | “Is it any wonder our kids are turning to drugs and crime? Parents are not parenting. They are more interested in earning money than spending time at home.” |

| Appeals (emotional) | Emotional appeals play on people’s feelings. | “Let’s be fair. We all have a right to justice. Everyone deserves a second chance.” |

| Emotive language | Emotive language refers to word choice. Specific words are used to evoke emotions and can be used to cause different reactions in the audience. | Outrageous, disgusting, foul, massive, awesome, fantastic, horrible |

| Evidence | Evidence can be presented as information, data, facts or statements to support a belief, opinion or point of view. | Some of the world’s leading marine biologists tell us that climate change is destroying the Great Barrier Reef. |

| Rhetorical question | A rhetorical question does not require an answer. It is used purely for effect | “Is it so shameful that Australian politicians might actually show their emotion?” |

| Tone | The tone reflects the way an author feels about an issue or subject. | Accusing, bitter, cynical, patronising, aggressive, calm, concerned |

Once students can recognise arguments and different persuasive techniques, the next step is for teachers to get them to identify such techniques in context and to consider the impact or effect of the strategy on the reader. This lies at the heart of the analysis of persuasive language, and is often what many students find challenging.

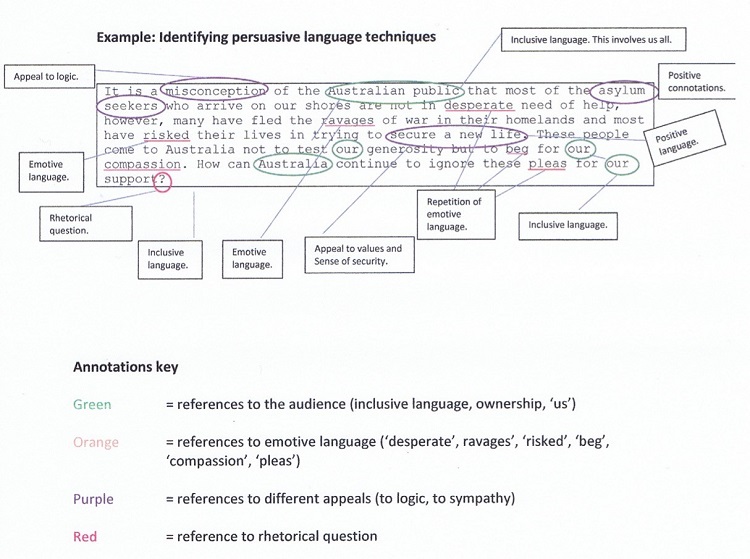

The sample below from a Year 10 student demonstrates how teachers can support students to identify persuasive language techniques through colour-coded annotations.

The final question that students must respond to when analysing persuasive devices is:

-

Why has the author used these particular words/visuals? What effect does the author want it to have on me?

The acronym

ATE can also be helpful to follow as an approach to analysis:

-

Argument – what is the author arguing?

-

Technique – what techniques does the author use?

-

Effect – what effect does each technique have on the reader?

Student sample using ATE acronym to structure a written response

-

Argument: Many Australians have a misunderstanding about the real reasons that asylum seekers are coming here.

-

Technique: ‘misconception’ is an appeal to logic, ‘Australian public’ uses inclusive language, ‘asylum seekers’ not refugees

-

Effect: Gets the reader to reassess their own beliefs about why asylum seekers want to live in Australia

In the opening paragraph of her letter to the editor, Angie Farrer argues that many Australians are unaware of the reasons that force asylum seekers to flee their homelands. Through an appeal to logic, she suggests that this is a ‘misconception’ and she keeps the reader onside as she explains the reasons why. By making reference to the ‘Australian public’, Farrer is inclusive of her audience on the one hand, but keeps them at a distance on the other. The impact of this technique is to get the reader to assess their own position on the place of asylum seekers in Australia, and as a result, to sympathise with the many people who come here because of war.

See,

VCELA459,

VCELY466,

VCELY467,

VCELY468,

VCELY469.

This strategy may be employed as an individual, pair or small group activity where students work together to identify each part of the ATE acronym. It can also be modified to support the reading of literary texts (VCELT461,

VCELT464,

VCELT466).

Using worked examples (reading and viewing, writing)

A worked example (HITS Strategy 4) provides students with a step-by-step solution to a problem or a process to follow. Worked examples are referred to in a variety of ways, including

- learning from examples

- example-based learning

- learning from model answers

- studying expert solutions (Ayres & Sweller, 2013).

By scaffolding the learning, worked examples support skill acquisition and reduce a student’s cognitive load. The teacher presents a worked example and explains each step. Later, students can use worked examples during independent practice as well as to review and embed new knowledge.

English teachers will often use worked examples to model the steps involved in planning and writing an essay. A teacher may use a worked example as a whole class activity that may be presented over a series of lessons. Practice and rehearsal of specific skills are at the forefront of the worked example.

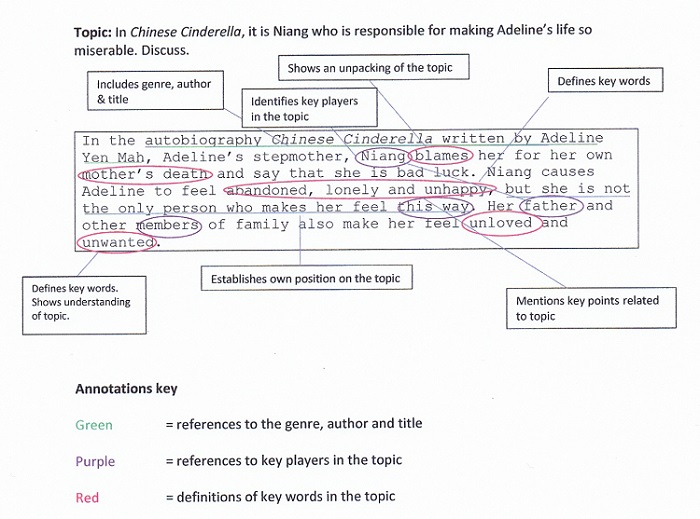

Example: Worked example of an introduction for a text response.

Points to include in an introduction for a text response:

- Mention the genre, author and title of the text

- Show an unpacking of the topic

- Define key terms if needed (but not as dictionary definitions, rather as synonyms to show understanding)

- Show your position on the topic

- Mention any key points related to topic

A Year 9 text response on Chinese Cinderella (1999) by Adeline Yen Mah

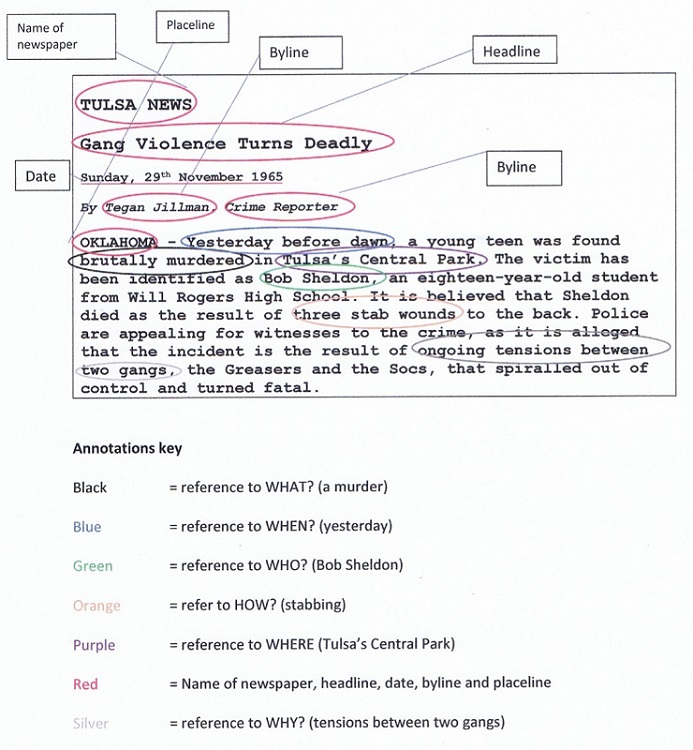

Example: Worked example of an introduction for an imaginative response to a text.

Points to include in an introduction for a news report:

- A headline (catches the reader’s attention, sums up the story)

- A byline (writer’s name and area of focus)

- A placeline (where the story begins)

- A lead (opening section that provides answers to: Who? What? Why? Where? When? How?).

An imaginative news report written by a Year 9 student studying The Outsiders (1967) by SE Hinton.

The worked example approach helps students understand how texts are structured for specific purposes and effects (VCELA429,

VCELT439,

VCELA433).

References

Ayres, P., & Sweller, J. (2013). Worked examples. In J. Hattie & E. M. Anderman (Eds.), International guide to student achievement (pp. 408–410). New York: Routledge.