Supporting students to get their knowledge ready for learning is an important stage in reading comprehension and links closely to the Victorian Curriculum (VCELY412,

VCELY443).

Activating prior knowledge (speaking and listening, writing)

Munro’s (2002) high reliability literacy teaching strategies shed light on the differences between students’ existing knowledge and the new knowledge they are expected to internalise when reading. This difference between existing and new knowledge is the source of many difficulties students face when reading.

Two activities that enable students to activate their prior knowledge before reading include:

- Thinking with prompts

- Using word clouds/brainstorms.

The examples below support reading Jasper Jones (Silvey, 2009) in a Year 9 or 10 class.

Thinking with prompts

Students are provided with visual, written or verbal prompts about an upcoming text.

These prompts might be a collection of images or visual representations of the larger themes in the text. In the case of Jasper Jones, the following visual prompt is an image that speaks to the theme of ‘scapegoating’.

Questions are used to encourage students to make connections between their existing knowledge and the knowledge that will be explored in the text.

Questions that could be used include:

- Have you heard of the novel or film, Jasper Jones?

- Have you heard of To Kill a Mockingbird?

- Have you heard the phrase ‘coming of age’ before? What do you think it means?

- What other Australian films have you seen? Which ones stand out to you

- Looking at the cover, what inferences can you make about the characters, plot and themes? Students may observe that both characters look worried, that a romance is a sub-plot, that the story takes place in a small town, and they may discuss the colours in the cover, including skin tones and the colour of the sky above each boy’s head.

While the teacher can lead the class in a discussion of these questions, students' responses could be collated in a digital collaborative space and then referred to as the text study progresses.

Word clouds and brainstorms

Word clouds and brainstorms are an easy but effective way for teachers to quickly establish what learners may know about a particular topic.

There are many online resources available that allow students to interactively create word clouds (see example below), or to collaboratively respond, record and revise question prompts before, during and after reading.

To initiate a word cloud:

- The teacher states a key word (or uses the cover of the novel as a prompt).

- The teacher asks students to record all of the words that come to mind when they think about that term.

- The teacher moderates student sharing as synonyms and examples are shared by students and added to the word cloud.

- The teacher takes note of student prior knowledge and can target future student learning (e.g. about historical context or genre conventions).

The activity can be altered so that students are organised into groups with each group focusing on a different aspect of the text that is to be read. Alternatively, groups of students could write responses on butcher’s paper or digital whiteboards and then rotate around the room, reviewing and adding to the notes written by the other groups.

Image created with

www.wordart.com

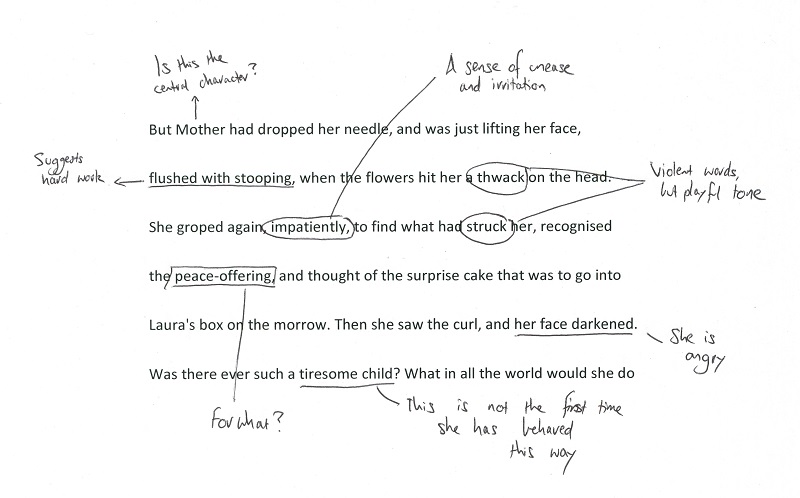

Annotating text (reading and viewing, writing)

English teachers often use annotations as a way to support students with their comprehension and to develop a closer reading of texts.

One way to do this is to guide them to identify the key words, quotes, sections or passages within the text, and makes notes as they go. The annotations form two functions, to help with understanding and to be a reference point for revision at a later stage of learning.

When students learn to annotate text, for example, by underlining key words or writing the main idea in the margin, which students can be guided to do on both electronic and paper texts, they should be provided the opportunity to talk to each other about the text using their annotations. This will help them to:

- further develop their interpretations

- challenge others’ interpretations

- explain the processes by which they came to their interpretations

- learn how others read and interpret texts.

Putting into words both interpretations and thought processes adds to students’ awareness of the strategies they are using and the characteristics of texts.

A teaching model of how to annotate a text is an important step in building students’ independence with their own reading and note-taking.

A set of step-by-step instructions about how to approach annotations is also crucial.

Annotations:

- Ask a question.

- Look for the answer to the question.

- Circle a word you don’t understand (look up its meaning).

- Underline an important quote (line or phrase).

- Make a connection (how does this relate to something else you’ve seen or read?).

- Give an opinion.

- Look for clues to help draw an inference.

- Retell what has been read (make summary note).

- Visualise a picture.

Curriculum links for the above example:

VCELT461,

VCELT465,

VCELY466,

VCELY467.

Literacy in Practice Video: English - Think-Alouds and Annotating Texts

The following video demonstrates how to use modelled reading with think-alouds and how to model annotations in a Year 7 English class.

This was a double lesson of English with team teaching. After reading the text and modelling text annotations, the learning focussed on the difference between formal and informal language. The teachers use text messages as an example of informal communication.

Teaching notes offer more details about this English lesson that included the learning intentions, rationale, Victorian Curriculum links, the literate demands and assessment, and the learning and teaching stages in this video segment.

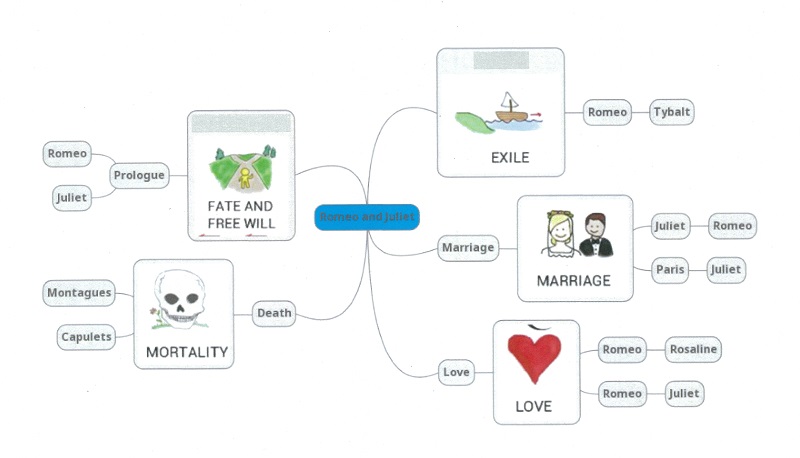

Concept mapping (reading and viewing, writing)

In concept mapping, students learn to identify important relationships that capture text structure and to represent these in a diagram (Armbruster & Anderson, 1980).

Mapping requires students to engage with meanings in text, to search for particular textual and linguistic features, and to transform these features into a diagram representation. The result is a student-produced diagram that uses symbols to capture interconnected textual features.

Armbruster and Anderson (1980) describe mapping as a technique which can be varied to suit the reader’s purpose. Students learn to search for key words or other linguistic or textual features and to make connections between these. Students are then introduced to symbols, which are used to map relationships between different features of the text.

Fisher, Frey and Hattie (2016) suggest that concept mapping is most effective when it is used as a tool for students to show their thinking and to organise what they know. In other words, a concept map should not be considered an end-product; rather, it is an intermediate step that students can use to complete another task (Fisher, Frey & Hattie 2016, p. 80).

The following concept map was produced by a Year 10 student to unpack the relationships between themes and characters in Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet (VCELY467,

VCELY468,

VCELY469).

Teachers can provide further scaffolded instructions to support students to elaborate on themes and identify key textual events and quotes to support later essay writing. Example instructions below.

For each:

- connecting line: write a word or sentence to describe the relationship

- character: identify an action or quote that demonstrates how they relate to the identified theme

- theme: list the imagery or symbolism that Shakespeare uses. For example, sun for Juliet.

Close reading (reading and viewing, speaking and listening)

Close reading is a method of engaging with literary texts. Snow and Connor (2016) define close reading as “an approach to teaching comprehension that insists students extract meaning from text by examining carefully how language is used in the passage itself” (p. 1).

Close reading supports students to explore the ways that ideas and viewpoints in literary texts come from different historical, social and cultural contexts. It also supports students to think about how these contexts may reflect or challenge the values of individuals and groups.

The main intention of close reading is to engage students in the reading of complex texts. Fisher, Frey and Hattie (2016, p. 89) outline four elements to support close reading:

- repeated reading of a short text or extract

- annotation of the short text or extract to reflect thinking

- teacher’s questioning to guide analysis and discussion

- students’ extended discussion and analysis.

Wheeler's (n.d.) six-approach to close reading

Wheeler (n.d.) offers a six-stage approach to close reading.

This approach is modelled using Shaun Tan’s ‘The Water Buffalo’ from Tales from Outer Suburbia (2008), to show how repeated readings can be used to support Year 8 or 9 students to read the text in a structured, specific and sustained manner (VCELT403,

VCELT438,

VCELT439).

First impressions

- What is the first thing you notice about the passage/s? What is the second thing?

- Students might observe the briefness of the story, and that they have many questions that are unanswered by the text.

- Do the things you noticed complement or contradict each other?

- Students might notice that the short length of the text causes details to be missing, such as what kind of advice the children asked of the Water Buffalo.

Vocabulary and diction

- Which words do you notice first? Why? What is interesting about this word choice?

Discerning patterns

- Does an image here remind you of an image elsewhere in the book? Where? What's the connection?

- Students may observe the similarities to the abruptness of ‘Tales from Outer Suburbia’ short story ‘Eric’, where a character is suddenly gone, and a similar sense of mystery surrounds them.

Point of view and characterisation

- How does the passage(s) make us react or think about any characters or events within the narrative?

- The teacher could frame this discussion as a list of questions for the buffalo, in response to the mystery caused by the omitted details.

Symbolism

- Are there metaphors? What kinds? How might objects represent something else?

- The teacher could pose this question as: Who do children often go to for advice? Who might the buffalo represent in their lives?

Lenses

- How can the meaning of words and sentences change when we look through a particular lens?

- Possible lenses could be: which words sound like they belong to a fantasy text, and which ones might sound more like a factual recount?

The six-stages don’t need to be in order. Furthermore, you may wish to include other activities to complement the six-stage approach.

What is important is that students are supported with multiple readings, each of which adds to the previous, with the end goal of a more complex understanding of the text.

Literacy in Practice Video: English - Comparative Analysis

The teacher in this video is engaging Level 10 English students in a comparative analysis of three texts in a close reading task. This video was recorded in a double lesson in preparation for a comparative essay task. The lesson begins with students reading independently, then moving into small groups to compare the texts and find evidence showing how individuals in these texts were trapped by social norms.

Teaching notes offer more details about this English lesson that included the learning intentions, rationale, Victorian Curriculum links, the literate demands and assessment, and the learning and teaching stages in this video segment. Sample text used in video for comparative analysis in a small group activity.

Decoding visual images (reading and viewing, speaking and listening)

Teaching students the metalanguage to speak and write about visual images is fundamental for them to be able to read, interpret and analyse visual texts.

According to Kress and Van Leeuwen (1996), visual images are read as ‘texts’ and contain a ‘grammar’, that is, a set of socially constructed resources to make meaning.

Metalanguage for visual analysis

For example, an advertisement billboard containing a static visual image with foreground and background, accompanied by printed language, in the form of a tagline and company name, contains a structure which guides how the advertisement is designed to be read by an audience.

In the digital world where students are increasingly exposed to a variety of multimodal and interactive texts, students require the language to be able to decode images as well as to make meaning from them.

Some of this language may be appropriated from the study of literary texts, however, new terms will also need to be introduced into the classroom which recognise the unique communicative capabilities of these texts. See the table on Metalanguage for Visual Analysis below.

Metalanguage for Visual Analysis

line

shape

size

proportion | colour

medium

light

shadow | perspective

positioning

framing

cropping

backgrounding

foregrounding |

Guided questions to discuss images

An effective way for teachers to introduce visual images to students is through the discussion of a still image. The teacher deconstructs the text with students, introducing and modeling the use of appropriate metalanguage. The deconstructed image may come from a class print text or may be a still from a film or moving image.

Analysis of an image

Sample student responses to questions about the image.

-

Where is your eye first drawn to? My eyes go straight to the girl in the middle of the image.

-

Describe the central figure. The girl in the middle of the image is a teenager who is reading a book. She has long, black hair. She is wearing a denim shirt and a pale pink summer skirt. Her eyes are looking down at the book she is holding in both her hands. She has a smile on her face.

-

How is the central figure framed? The girl is framed by some bookshelves on both sides of the room she is about to enter. There is also a tree trunk and its leaves at the entrance of the room which is close to her right shoulder. Some of the branches form an arch over her head.

-

What are the details in the

background? There is a winding path behind the girl that leads to the room she is about to enter. The path runs through the middle of a forest.

-

What are the details in the

foreground?There is a brick floor inside the room where the girl is standing. There are also some books scattered on the floor.

-

How is colour used in the text? This image contains soft colours inside the room that are mainly grey, but with slight hints of other colours on the spines of the books. As my eye moves from the inside of the room to the outside, the colours become stronger and bolder. The colours of green and brown stand out. The girl’s clothes also contrast with the muted colours in the room.

-

How are light and shade used? There are two light bulbs positioned on the ceiling in the room. One light points down towards the girl. This helps to make her the centre of the image. The other light faces one side of the bookshelf and it lights up the books so that the colours are slightly bolder.

-

From whose perspective is the text presented? It is as if a person is standing opposite the girl at the other end of the room looking inwards.

Using see, think, wonder, like to read a visual image

Students are provided with a photograph, illustration or artwork to view. Teachers ask students to record their initial reactions to the image through questions such as:

- I see… (literal level of comprehension)

- I think… (inferential level of comprehension)

- I wonder… (inferential level of comprehension)

- I like/dislike… (evaluative level of comprehension)

Initial student reactions

-

I see a girl standing in the doorway of a room with books in it. There is a path and trees outside. Some of the trees are on the inside.

-

I think the girl enjoys reading because she is looking down at the book and she has a smile on her face.

-

I wonder why the girl is there and what she is going to do when she goes into the room.

-

I like the way the colours get stronger as you look out into nature. It reminds me of a picture in a fairy tale.

These visual literacy strategies support curriculum objectives, in particular,

VCELT407,

VCELY411,

VCELT418)

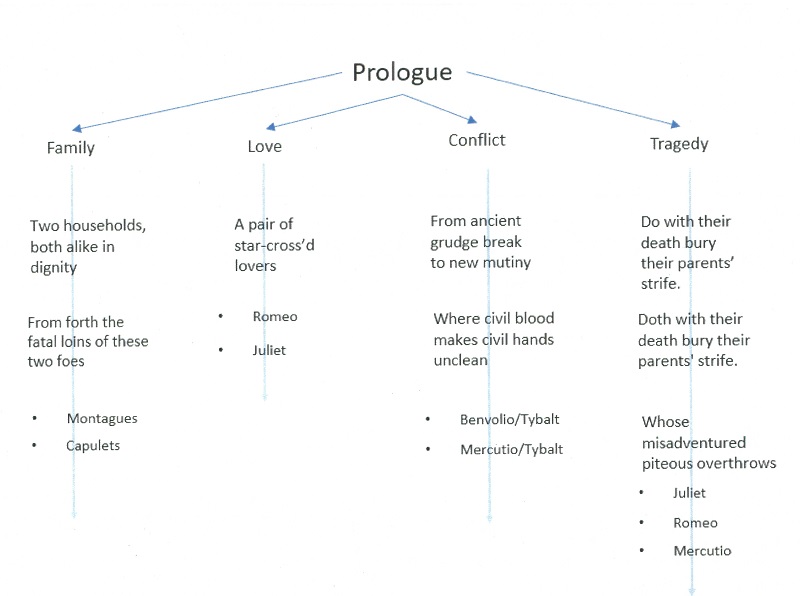

Flow-charting (reading and viewing, writing)

Flow-charting is a tool for displaying the relationships between the features of a text. The flow-charting technique developed by Esther Geva (1984) requires a reader to use a nodes-relations system to represent content and ideas. Nodes are points in a diagram or network that branch out to other nodes and demonstrate relationships.

Flow-charting can be used to demonstrate connections between the ideas or themes in texts, the literary features which help realise these themes, and the structures that hold texts together. Depending on the focus of the flow-charting activity, it can be used to support student learning in relation to the following sub-strands of the Victorian Curriculum 7–10: English:

- Text structure and organisation

- Responding to literature

- Examining literature

- Expressing and developing ideas

- Interpreting, analysing, evaluating.

Flow-chart in practice

For example, a teacher might use the following instructions to support students to produce flow-charts when analysing a literary text:

- Identify the key themes in this text, place them at the top of your page.

- List three events from the text that the author uses to explore each theme.

- Link individual characters and quotes from the text that relate to each event.

The following flow-chart captures the ideas in the prologue to Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, as well as the textual knowledge that contributes to the formation of these ideas (VCELA473,

VCELY467,

VCELY469).

Guided questions (reading and viewing, writing)

Guided or guiding questions are questions provided to students, either in writing or spoken verbally, while they are working on a task. Asking guided questions allows students to move to higher levels of thinking by providing more open-ended support that calls students' attention to key details without being prescriptive. This activity is part of Questioning (HITS Strategy 7).

Guided questions to support teachers

Teachers can use guided questions to support students’ comprehension of texts (VCELY378,

VCELT438). This example provides questions that could be used when reading fiction and non-fiction texts. They can also be adapted for a set text.

This activity could be used for individual responses to a text or as a group activity lucky dip.

- The teacher presents each guided question on a separate piece of paper.

- The teacher asks students to select a random question from the set.

- The teacher asks students to respond to the question individually.

- The teacher asks students to share their responses.

- The teacher guides students through discussion about each question.

Worksheet example of Guided Questions

Worksheet example of Guided Questions

Name any other stories that this story reminds you of. How did that connection help you to understand the story better? | How are you alike or different from the main character in the story? |

How did the story make you feel? When have you felt that way in your real life? | How does what you know about this type of text help you better understand the story? |

What other stories have you read with similar characters or themes? How did that connection help you better understand the story? | What lessons did you learn in the story that can help you in your real life? Explain. |

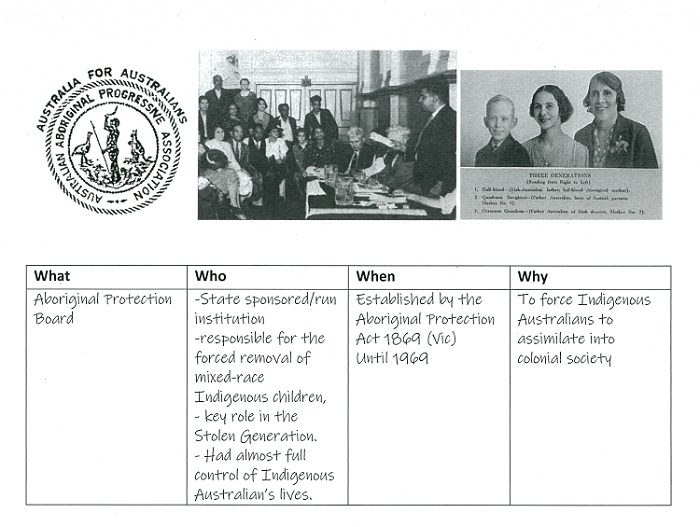

Initial field building (reading and viewing, speaking and listening)

Initial field building involves finding out what students know about a topic and then working with them to develop shared understandings which will inform their selection of certain subject matter to include in their writing (Derewianka, n.d.).

In short, the purpose is to develop subject matter that will be the focus of student writing. The more students know about the topic, and the more language they use to express this knowledge, the better prepared they will be for writing with purpose and precision.

Building the field should be a social activity which include opportunities for conversations. While talk will often focus on information found in written and multimodal texts, it is important that the emphasis is on students’ spoken language.

See

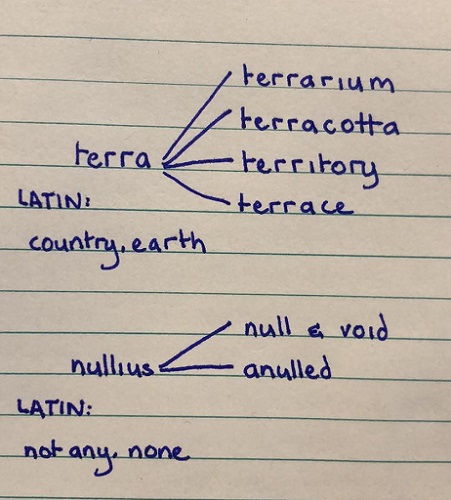

building the field or context for a range of common tasks. The student work samples below demonstrate how two of these tasks can be used to build the field for Year 10 students studying Claire G. Coleman’s Terra Nullius (2017).

Research task about the Aboriginal Protection Board, a key aspect of understanding the text (VCELY466,

VCELY469).

Building vocabulary through the study of Latin root words within the title, ‘Terra Nullius’ (VCELA475)

Importantly, building the field is not a one-off stage or strategy. Rather, teachers should continue to support students to develop their understanding of a topic, including their vocabulary, as they progress through various stages of writing.

Literal, inferential and evaluative questions (reading and viewing)

Reading comprehension is required across three levels

- literal

- inferential

- evaluative.

Literal comprehension occurs when the reader understands information that is explicitly stated within the text.

Inferential comprehension involves the ability to process information so as to understand the underlying meaning of the text (VCELY469). This is sometimes called ‘reading between the lines’.

Evaluative comprehension occurs when readers judge the content of a text by comparing it with:

- External criteria - where it agrees with what is generally known or expected

- Personal criteria - how it fits with what individual readers know and what they value.

Teachers can use questioning which targets all levels of reading comprehension using literal, inferential, evaluative (L.I.E.) questions.

The following L.I.E. questions could be used to support Year 8 students’ understanding of the below cartoon, and demonstrates how a teacher might move a student from surface level to deep level understanding (VCELY411,

VCELY412).

Literal

- Who are the characters in this scene?

- What suggestion has the girl made to Miles?

Inferential

- Where is Miles?

- Why can’t we see him?

- What is the boy on the right looking at?

Evaluative

- What does this cartoon reveal about the writing process?

- What does the reader need to know about stories to understand the comic?

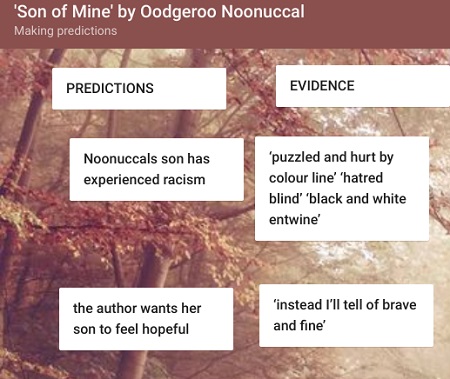

Predicting (reading and viewing, speaking and listening)

Good readers make predictions about what is coming up based on available information, whether in the text or their own experiences (both lived and textual).

These predictions change as the reader progresses through a text and new information becomes available.

Teachers can enhance reading comprehension by providing opportunities for students to make predictions prior to, and during reading (VCELY412,

VCELY443).

The benefits of predictive activity are well-established (Pearson & Gallagher, 1983), and highlight the importance of drawing connections between: prior knowledge, predictions and reading content.

Predicting with classroom discussions

In Parkin & Harper’s (2019) work on teaching literacy through literature, classroom discussion is used to assist students to make predications as they read. Teachers support students in identifying clues in the text.

The teacher has students role-play the author as they describe these ‘clues’ for prediction that the author has left. The example below demonstrates how this activity could be used in a Year 7 class reading one of Paul Jennings short stories, “Nails”, from Unbearable (1990).

Teacher: Who would like to be Paul Jennings today? Come on down Paul Jennings, and tell us about the foreshadowing in your story.

Student: Well, I’ve put in lots of foreshadowing in the story to give you clues about how the story ends.

Teacher: So Paul, could you perhaps explain to the audience what foreshadowing is exactly, because I think some of them aren’t sure.

Student: Foreshadowing is little clues that I put in the story. Like when you’re hiding and other people can only see the shadow. You know someone is there, but you can’t exactly see them.

Teacher: Ah yes, thanks. Does that help, audience? Keep going, Paul. What clues did you give?

Student: So I wanted the reader to know that the end of the story was going to be about water. So when Lehman looks at his mother’s photo, she’s got a gold clip with pearls in, because pearls come from the sea.

(Parkin & Harper, 2019, p.51)

This activity guides students in making informed predictions about the plot, but also supports their understanding of the author’s writing skill by identifying the author’s purpose achieved (in this example, leaving clues to foreshadow a plot twist). This activity also models how to locate textual evidence and make inferences from clues.

Predicting with guided writing

Another way for students to engage in prediction is adapted from Hansen (1981). The teacher can ask students to:

- share what they know about the circumstances likely to be faced by those characters in the narrative

- predict what the characters would do when confronted with unfamiliar situations in the stories that were yet to be read

- write down their prior knowledge answers and their predictions

- write a paragraph interweaving their prior knowledge and predictions to strengthen their understanding that reading comprehension comes from what one knows and what is in the text.

Predicting with guided questions

Another way to engage in predicting work with students is to expose them to preparatory aspects of a text and to use questioning to anticipate other parts of the text.

For example, students who are about to study a new novel might be asked by their teacher to make predictions after the teacher has:

- Read the title and blurb aloud.

- Shown the class a map that captures the main events.

- Provides a description of the main character.

- Read aloud the opening sentence or paragraph of one.

Similar questions can be asked for any text. For example, when introducing the poem ‘Son of Mine’ by Oodgeroo Noonucal to a Year 9 class, a teacher might activate student prior knowledge and prediction by asking the following questions:

- What do you already know about Oodgeroo Noonuccal.

- What do we know about Australia’s history that might help us guess what an Indigenous poet might tell her son?

- The first line tells us about the son’s ‘troubled eyes’. Can we predict what might be troubling her son?

Web-based brainstorming apps, such as Answer Garden and Padlet, can be set up to enable students to track their predictions, and the evidence they collect both before and during reading.

Curriculum links for the above example:

VCELA432,

VCELT435,

VCELT436,

VCELT440.

Schematising (reading and viewing, writing)

A Schema is a cognitive or mental framework that we can construct in our mind to interpret or re-represent aspects of our world, including features of texts.

Visualisation can also take place without the need for the reader to produce any text. Students can be encouraged during both teacher read-aloud and silent or paired reading to pause at specific points in the text to imagine what has been read. This could require students to visualise a process, and then verbalise or draw their mental image. Or, students could be encouraged to use mental imagery to add visual characteristics to a scene or feature of a print text, improving their comprehension (VCELY411,

VCELY443).

After reading aloud to Year 8 students the prologue to Glenda Millard’s A Small Free Kiss in the Dark (2009), the teacher might ask students to close their eyes and picture:

- Tia and the baby: What are they wearing? What are they doing?

- the carousel: How big is it? What state of repair is it in? What colour is it? What do the carts look like?

- the fun park: What other rides are there? What might the ground look like? Students are then encouraged to describe and justify their visualisation of the text. The teacher can encourage students to use evidence from the text and their own experiences to validate their interpretation of the text.

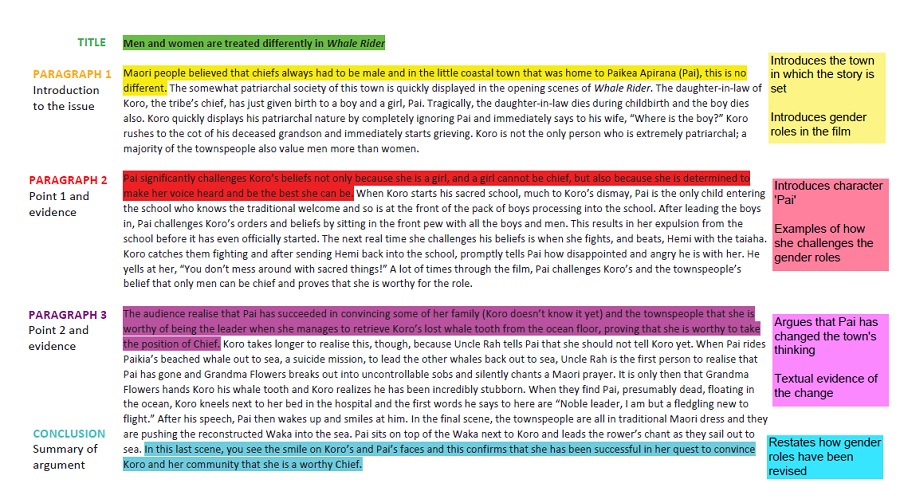

Using model texts to teach genre (reading and viewing, writing)

Before students are asked to produce a particular text, it is vital that they learn about the features of that genre (Derewianka, n.d.). This marks a shift away from the content of the writing, to the form, or craft, of writing.

Sometimes called ‘modelling’, explicit learning about genre provides students with knowledge about the linguistic and structural features of the text. This can include explicit teaching about the stages of a comparative essay, persuasive text, or specific forms of text response.

Each genre unfolds in particular stages and contains distinctive patterns. Learning about the genre allows students to identify the characteristic stages a genre contains in achieving its purpose (Derewianka, 1990).

For a range of strategies that teachers can perform with students when working with model texts for the purpose of learning the genre, see

building the field or context. Below are two student samples that show how text marking and deconstruction can be employed in the English classroom.

Literacy in Practice Video: English - Using Worked Examples

In this video, the teacher uses a model text ‘The Simple Gift’ to support a class of year 8 students in developing the skills they need to write a comparative paragraph. This teacher offers effective strategies to engage students in the process of deconstructing and co-constructing text that includes developing a metalanguage for students to talk meaningfully about the structure of the comparative text (e.g., comparative words, text connectives and conjunctions).

Read the in-depth notes for this video.

Text marking

Annotating a text as a class can be a useful strategy to highlight different stages of the text, their purposes, and key features of the genre. ‘Text marking’ (Parkin & Harper, 2019) can be done collaboratively using a physical interactive whiteboard, or through interactive whiteboard web-based software through which all students can collaborate.

Year 9 model text response that has been marked up during a teacher-led discussion (VCELY449,

VCELY450,

VCELY451). Image created using online software.

Group annotation can also be used to find or highlight key words, phrases or sentences which assist students’ understanding of the text, and looking for patterns across texts.

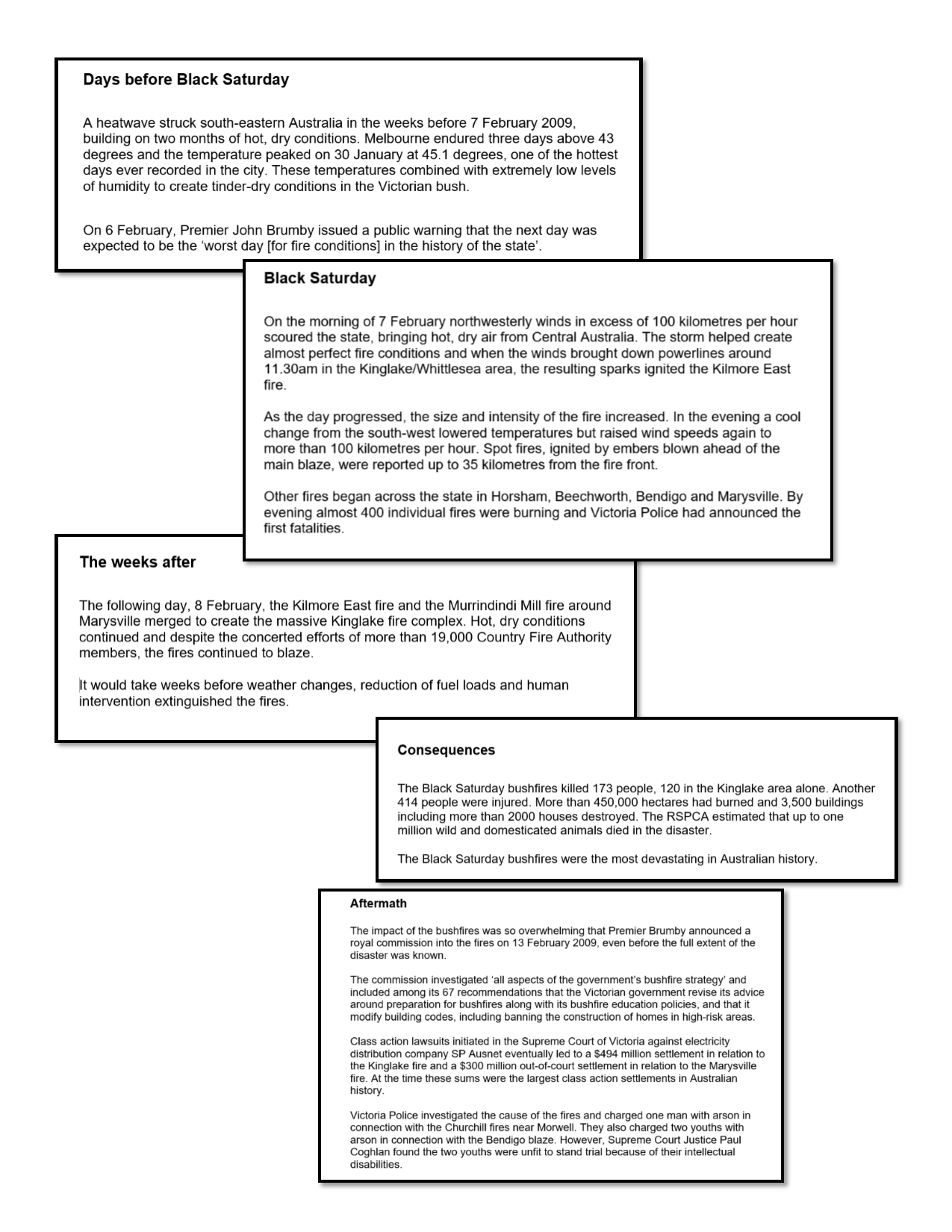

Sequencing

Deconstructing and reconstructing the text can be useful to:

- explain how the parts of a text work together

- explore sequencing and cohesive links, as well as markers of time.

As with text marking, teachers can jointly deconstruct a text with students and explicitly teach textual features. As students become more familiar with genre features, they can move towards independent deconstruction and reconstruction.

It can often take repeated encounters with model texts for learners to internalise their features. Students should be provided opportunities to encounter and revisit genre features on multiple occasions so that understanding is reinforced (HITS Strategy 6: Multiple exposures).

The following worked example is from a Year 7 class and uses the online article, ‘Black Saturday bushfires’, published by the National Museum of Australia (VCELA380). Teachers could adapt this activity to support learning related to text structure and organisation at any level from 7 to 10.

For this strategy:

- Students were given printed copies of the article, cut into sections.

- Students were asked to highlight key words that indicate sequencing (such as ‘before’, ‘after’ and ‘aftermath’)

- Students used these key words to arrange the sections in an order that made sense.

View full size image "Composite Graphics".

- Students reviewed each other’s reconstructions, justifying their choices and providing feedback to one another. This offered opportunities to discuss more complex aspects of structure, such as the ordering of ‘consequences’ and ‘aftermath’ that do not have a clear hierarchy to indicate where they should be arranged.

Additional tasks using model texts are:

- asking questions which require re-reading

- cloze activities creating flow charts or matrices to reflect connections between meaning and structure

- contrasting purpose and structure with a different genre

- For example, the information from the article on the NMA website (above) could be reworked into a brief fictional narrative, and the sequencing of events might be affected by the literary device of ‘flashback’ and ‘flash forward’ (VCELT385,

VCELT386,

VCELY387)

- finding other examples of the genre to compare

- For the example above, this could include other recounts of historical events that reflect on the aftermath, and integrate individual experiences into the text to varying degrees (VCELY378,

VCELY379).

References

Armbruster, B. B., Anderson, T. H. (1980). The effect of mapping on the free recall of expository text (Tech. Rep. No. 160). Champaign: University of Illinois Press.

Derewianka, B. (n.d).

A teaching and learning cycle.

Derewianka, B. (1990). Exploring how texts work. Newtown: Primary English Teaching Association.

Fisher, D., Frey, N., & Hattie, J. (2016). Visible learning for literacy, grades K-12: Implementing the practices that work best to accelerate student learning. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Geva, E. (1983). Facilitating reading comprehension through flowcharting. Reading Research Quarterly, 18(4), 384–405.

Hansen, J. (1981). The effects of inference training and practice on young children's reading comprehension. Reading Research Quarterly, 16, 391–417.

Kress, G., & van Leuween, T. (1996) Reading images: The grammar of visual design. London: Routledge.

Munro, J. (2002). High Reliability Literacy Teaching Procedures: A means of fostering literacy learning across the curriculum. Idiom, 38(1), 23–31.

Parkin, B., & Harper, H. (2019). Teaching with intent 2: a literature-based literacy teaching and learning. Marrickville: Primary English Teaching Association Australia.

Snow, C., & O'connor, C. (2016). Close reading and far-reaching classroom discussion: Fostering a vital connection. Journal of Education, 196(1), 1-8.

Wheeler, K. (n.d).

Close reading of a literary passage.